|

|

For many SaaS makers, building feels like progress because it’s familiar and controllable: you decide what gets done, see the work add up, and at the end of the day there’s usually something tangible to show for it.

Selling doesn’t offer the same certainty. Pricing raises uncomfortable questions. Feedback introduces doubt. Launching forces commitment — to an audience, a problem, and a message — before everything feels settled.

So building continues:

- Scope expands

- Features stack

- The product starts to feel more complete, but less defined

Without real users making real decisions, it becomes harder to answer basic questions: Who is this actually for? What problem matters most? How should it be positioned?

We’ve seen this pattern repeat across early-stage SaaS teams and have heard the same tension echoed by founders who’ve already shipped through it.

In this piece, we draw on insights from David Kemmerer (CoinLedger), Jason Levin (Memelord), and Jonathan Matson (Crew Console), who took very different paths to launch but ran into similar traps and came out the other side successfully.

Why Overbuilding Fails as a Validation Strategy

Launching often gets framed as something that requires confidence or external validation first.

Jason Levin, founder of Memelord and former Head of Marketing at Product Hunt, didn’t wait for either before shipping:

“The number one thing I wanted was usefulness for myself. I built it because I wanted it to exist.”

In Jason’s case, that usefulness was very literal.

He was working as a social media marketer and wanted to be first on emerging meme trends, so he built a scrappy AI scanner that alerted him to what was taking off. That internal tool eventually became “Meme Alerts” — one of Memelord’s core features.

His rule was simple: if the product solved a problem he personally felt every day, it was worth shipping. Finding other people like him came later, and, as he puts it: “You’re not that unique.”

Still, it’s easy to assume a more complete product will be easier to sell. In practice, completeness rarely answers the questions that decide whether a product survives.

Until someone is willing to part with money, you’re left guessing.

For Jonathan Matson, co-founder of Crew Console, “launch-worthy” didn’t mean feature-complete. It meant the product could support real use.

“For us, the basics had to work — scheduling, task tracking, and crew communication. Onboarding needed to be simple, and core dashboards had to make sense.”

His team deliberately left out advanced reporting, payroll integrations, and complex dashboards at launch. Jonathan’s goal was simple:

“Crews needed to complete real work without friction. Anything that didn’t directly support that outcome could wait.”

This matters because most SaaS businesses don’t grow explosively once they launch. The median B2B SaaS company grows at around 25% year over year, whether it’s bootstrapped or funded.

Shipping something “ready” doesn’t unlock growth on its own. Usage and retention do.

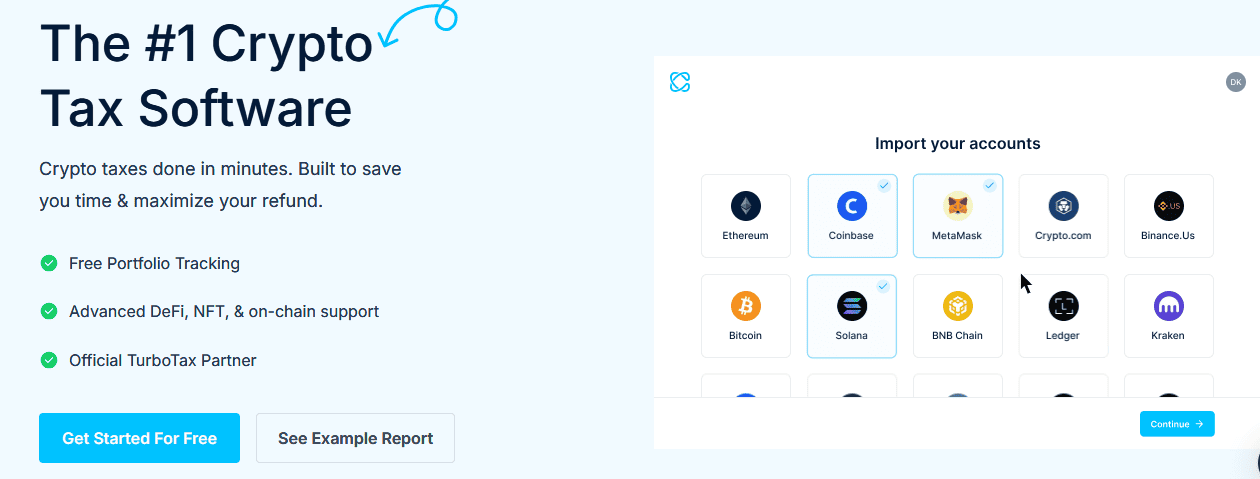

David Kemmerer, CEO of CoinLedger, learned this early. Before launching, his team built features to cover every possible tax edge case, worried a narrower product would be rejected. Looking back, 99% of their users didn’t need those features.

David later realized their caution had caused them to miss an entire tax season — a window where demand was guaranteed and urgency was built in. They earned nothing, despite months of work spent polishing features that ultimately didn’t change outcomes.

“That one more feature you believe you need is for your psychological safety and not a requirement of your product.”

Why Usage Beats Praise When Validating a SaaS Product

Validation begins when people start making choices: paying, coming back, adapting their workflow, or walking away. Each of these decisions points you toward what to change, improve, or stop.

- One paying user can teach you more than dozens of signups

- Repeat use matters more than opinions

- Friction exposes what people actually value

- Retention beats enthusiasm because returning users reveal whether the product fits into a workflow

David saw this almost immediately after launch. In their second week, CoinLedger received an angry email from a user who found a bug in their tax report, asking how to pay to get it fixed.

Though the software was flawed, the user didn’t want to leave. That single interaction was more informative than the praise that came before it.

Earlier, hundreds of people had told David’s team the product was “much needed.” It felt encouraging. A month later, they lost 4% of their subscribers. Praise hadn’t translated into sustained use or willingness to keep paying.

The gap between encouragement and retention is common. Benchmarks reveal that SaaS businesses with a net revenue retention rate over 100% grow about 54% a year, compared to roughly 12% for those with retention in the 60%–80% range.

This proves that retention, not early excitement, correlates with momentum and sustainability.

For early products, this means watching behavior under friction:

- Do users return after the first session without reminders or onboarding emails?

- Do they accept the price before everything is polished?

- Do they keep using the same core workflow once setup friction is gone?

Even no traction is information. If no one converts, churns immediately, or ignores a feature you thought mattered, that’s the signal.

Actions speak louder than interest and payment makes the signal unmistakable.

Jason saw this firsthand when he priced Memelord at $6.90 per month or $69 per year. Not because it was “correct,” but because he thought pricing orthodoxy was mostly nonsense.

Users tweeted about it, talked about it, and — most importantly — paid.

Jason’s view is blunt: there’s no perfect price, and you can always change it later. What matters early is getting people onto the product and watching what they do once money is involved.

This is where scope comes into the picture.

The One-Problem MVP Approach

Early-stage products are easiest to validate when they solve one specific problem.

Jason calls this a Minimum Useful Product.

He didn’t know how to code, so instead of waiting or finding a technical co-founder, he launched Memelord as a paid daily meme newsletter paired with a shared Google Slides deck. Subscribers received memes by email, then jumped into Slides to edit them.

Jason describes it as “the jankiest thing ever.” But it worked.

Hundreds of people paid, which created enough momentum to justify building the actual product later. In hindsight, he calls it “probably the stupidest MVP ever,” but without it, Memelord wouldn’t exist.

Once Jason saw people were paying, he hacked together the first real version of Memelord using no-code tools, eventually growing to roughly $100k ARR without hiring a single engineer.

Only after proving demand did he raise funding and bring in a technical team — the opposite of the “build first, validate later” playbook.

Jason’s story is a great lesson in not letting overbuilding hold you back.

| One-problem MVP | Overbuilt MVP |

| Solves one concrete job (e.g. generate a compliant tax report) | Tries to cover multiple workflows (reporting, planning, edge cases) |

| Feedback is easy to interpret (users succeed or fail at the core task) | Signals are mixed (usage spreads across features with no clear pattern) |

| Pricing and value are clear (users pay for one outcome) | Value is spread thin (pricing reflects bundled possibilities, not outcomes) |

| Failures are obvious and actionable (users get stuck at the same step) | Problems hide behind scope (issues are masked by optional features) |

| Signal is immediate (small changes show up clearly in usage and revenue) | Signal is delayed (it’s unclear what drove changes in usage or revenue) |

Robert Abela, founder of Melapress, frames the above in terms of signal quality.

In his experience, narrow scope produces clearer traction. He distinguishes between signals that reflect real use and those that feel encouraging but don’t drive decisions. For example:

- Strong signal: a support ticket describing a real workflow where the user can’t complete the task

Weak signal: praise with no follow-up usage or context - Strong signal: a feature request tied to something a user is actively trying to do

Weak signal: feedback that isn’t grounded in an attempted task, with no behavioral context - Strong signal: users returning during beta with specific questions

Weak signal: high traffic with no installs or activation

Robert’s distinction is exactly why scope matters early. “There’s a difference between what users say and what they’re actually willing to pay for.”

Focus on:

- One problem

- One core outcome

- Only the features that directly support it

The goal is to surface clear signals that lead to confident decisions. Anything else can wait.

See also: MVPs That Matter: How to Ship Fast, Stay Focused, and Build What Users Actually Need

What a Low-Stakes Launch Can Look Like

Small, focused launches work because they force assumptions into the open quickly.

Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup and a longtime advocate for evidence-driven product development, has made the same point for years: progress comes from seeing how people behave when something is live, not from extending internal debate or refinement.

“The only way to win is to learn faster than anyone else.” — Eric Ries, The Lean Startup

A small launch is most useful when it creates observable outcomes quickly and cheaply:

| What to design for | What it reveals early |

| A single core action |

Whether users can complete the paid workflow end-to-end without guidance. CoinLedger users consistently went straight to “Generate Report”, ignoring secondary features and making it obvious which action mattered. |

| Limited launch surface (invite list, niche channel, time-boxed release) |

Where users get stuck, confused, or drop off. Narrow launches (for example, targeting a single professional niche or workflow) surface |

| Minimal supporting features |

Which features are actually used versus assumed useful. CoinLedger’s tax planning tools saw little engagement — a clear signal to delay “nice-to-haves.” |

| One clear path to payment |

Whether the problem is painful enough to justify a decision. Urgency shows up immediately through completed payments, abandonments, retries, and payment-related support requests. These signals are surfaced naturally once checkout and billing are in place (which is exactly what tools like Freemius provide). |

Designed this way, a small launch turns user behavior into signals you can act on immediately, instead of problems that get lost in scope.

At CoinLedger, those same signals exposed how much effort had gone into scaling long before demand justified it.

“My advice is to delay automating infrastructure and scaling. We wasted a lot of time and energy building for a million users at the start, when we only had twenty. If the demand is not overwhelming, automation will be an expensive distraction.” — David Kemmerer, CEO of CoinLedger

The takeaway isn’t “don’t plan for growth.” It’s that premature scale is a form of avoidance. Until demand is unmistakable, anything that doesn’t help users complete the paid workflow is an expensive distraction.

Iteration Driven by Reality, Not Preference

Jason no longer treats launch as a verdict at all. In his view, “launch day” is mostly noise.

What matters is if users return, pay, and integrate the product into their day to day.

“Looking at launch data is kind of pointless. Who cares if we get 10M views? Obsessing over day-one spikes or viral moments is an ego trap.

Seeing how users love our product makes every day launch day.”

When you see launch this way, iteration stops going after vanity metrics and starts responding to behaviour. For Crew Console, that meant focusing on active usage instead of surface-level traction.

One early assumption didn’t survive contact with real users.

Jonathan says, “I expected teams to rely heavily on analytics dashboards. Instead, most crews worked almost entirely from mobile devices. That insight reshaped priorities: mobile access, reliability, and speed mattered more than deeper analytics early on.”

Without paid usage in real environments, that shift would have taken far longer to uncover.

Turning Usage Signals Into Iterative Action

Prioritize changes that unblock the core action:

Any step that keeps users from reaching activation — like completing a key workflow early — should take priority. Many SaaS teams explicitly measure time to first meaningful action (often within the first week) to judge fit and guide iteration.

- David shares an example: “If a hundred users asked for cosmetic improvements but ten couldn’t complete a paid task, the blocked workflow always won. Paying users made friction visible in financial terms, not popularity.”

Ignore single-instance requests:

One-off suggestions are common but misleading. In SaaS, real priorities emerge only when the same issue appears across multiple users and affects the core flow. Isolated requests often reflect edge cases, not product direction.

Fix where users deviate repeatedly:

Repeated detours or workarounds — like dropping out of a process before reaching the key outcome — are stronger signals than standalone comments. For example, SaaS teams use product funnels and cohort analysis to see where users fail to activate, and iterate on the steps with the largest leaks.

- Paid users also surfaced priorities that Jonathan hadn’t anticipated. “We thought people would use analytics dashboards more, but most worked almost entirely from mobile so we streamlined mobile workflows instead.”

Use small, isolated changes to test hypotheses:

Make one change at a time so cause and effect stay clear. David shared that batching fixes made it harder to tell what actually improved outcomes, while small, focused changes clarified what moved completion and retention.

All of this is easier when your tooling supports and handles the mechanics of the full journey — from launching to learning to scaling.

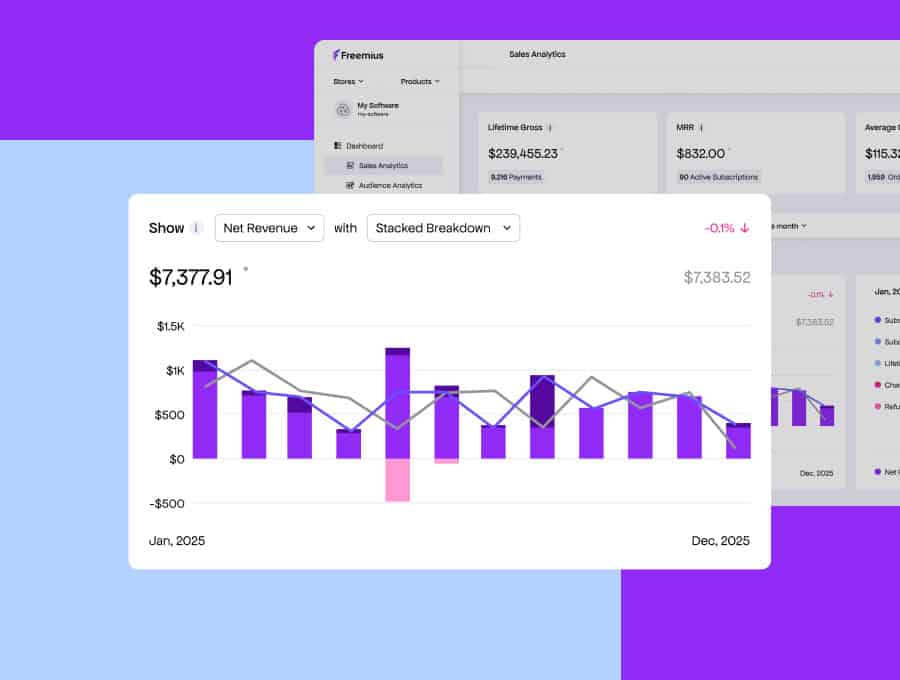

Freemius: The Early-Stage Validation Layer

Early-stage SaaS makers learn fastest once customer behavior and payment decisions are in play.

Freemius enables this by giving you a working checkout and sales engine from day one, so you don’t waste weeks building billing infrastructure before you can validate demand.

With Freemius you can:

- Start selling in minutes — embed checkout links or modal flows without custom billing logic and begin validating product-market fit with paying users.

- Track real usage and revenue signals — see what customers actually buy, how often they upgrade or churn, and which plans perform best, so you learn from behavior, not guesswork.

- Avoid operational distractions — Freemius handles payments, VAT/tax compliance, fraud protection, subscriptions, and recurring billing so you can focus on product improvements.

- Tap swift, context-aware support — responsive help from technical and strategic developers on the Freemius team reduces downtime and keeps your launch window alive.

- Lean on a community of fellow makers — over 2000 software entrepreneurs share insights, early feedback, niche validation, playbooks, and early partnership opportunities like integrations, referrals, and cross-promotions.

Instead of delaying monetization until everything feels perfect, Freemius helps you start selling early so pricing, demand, and retention become things you can learn from as you go.

Launch to Learn What Matters (Without Going It Alone)

Across Jason, Jonathan, David, and Robert, the pattern is consistent: progress starts when users are forced to make trade-offs — whether to pay, whether to return, and whether your product earns a place in their workflow.

You don’t need a finished product to get there. You need one clear problem, a path to payment, and the willingness to respond to user behaviour.

If you’re stuck one feature away from shipping, or unsure how to validate demand without taking on unnecessary risk, don’t delay it to another sprint.

Book a discovery call with Freemius founder and CEO Vova Feldman to talk through your product, your launch, and how to start learning from customers sooner.